Recently, I read the famous 2013 Google paper Tail at Scale. And boy oh boy was it an enjoyable read. It was fascinating to read how such a simple idea could be used in such an elegant way to reduce latency in distributed systems.

And in this post, I’ll discuss my golang implementation of the paper. But first, let’s discuss the paper itself.

What was the problem discussed

1. Large services make parallel RPCs

A single user request to Google Search fans out to hundreds of machines, for tasks like:

- fetching index shards

- querying ranking models

- retrieving personalized data, and more

2. The end-to-end latency = the slowest sub-request

If even 1 out of 100 internal requests encounters a momentary slowdown (a straggler node),

then 1 out of 100 user queries becomes slow — because the overall response waits for the slowest component.

3. Even tiny tail probabilities blow up at scale

If each shard server has a 99% chance of replying within 10 ms, then for a request that fans out to 100 shard servers:

$$ P(\text{all reply within 10\ \text{ms}}) = 0.99^{100} \approx 36% $$

Meaning:

- 64% of total requests become slow,

- even though each server is 99% reliable.

This is the core phenomenon:

“Tail latencies amplify dramatically as systems scale.”

But why does variability in response time exist?

1. Contention & Queuing

- Temporary CPU overload

- Memory pressure / GC

- Network congestion

2. Background daemons & OS tasks

- kernel flushes

- disk checks

- VM migrations

3. Hardware variability

- thermal throttling

- slow NICs

- SSD hiccups

4. Multi-tenancy

- noisy neighbors

- cloud workloads interfere

Solutions proposed in the paper

1. Hedged Requests (Speculative Retry)

Send duplicate requests if the first one is slow.

Strategy:

- Send the request normally.

- If no reply arrives after (say) the 95th percentile latency, send a backup request to another replica.

- Use whichever response arrives first.

Notes:

- Keep the rate of backups small to avoid overloading the system.

- Works extremely well in practice.

2. Tied Requests

A refinement of hedged requests:

- Send the request to two servers simultaneously.

- The server that detects its peer has replied cancels its own work.

This reduces redundant computation while still mitigating tail latency.

3. Request Slicing

Break large operations into smaller independent pieces (e.g., finer shard ranges).

This reduces the impact of any single slow piece.

4. Better Load Balancing

Use smarter, tail-aware routing:

- tail-aware load balancing

- queue-aware routing

- track nodes with consistently poor 99th percentile performance

- avoid overloaded or noisy hardware

Useful techniques:

- Power of Two Random Choices

- Least-loaded or latency-feedback routing

5. Micro-partitioning

Create many small shards instead of fewer large ones.

Advantages:

- better parallelism

- better isolation

- faster hedged retries

- ability to skip or reroute small slow pieces

6. Predictive & Proactive Techniques

- Track per-node tail latency history

- Penalize or avoid nodes that exhibit bad tail behavior

- Maintain statistics to predict node performance under load

7. SLA-aware Admission Control

Reject, shed, or throttle new requests when nearing overload,

to prevent catastrophic tail latency spikes.

8. Fault Isolation & Redundancy

- isolate hot or overloaded partitions

- use replication

- degrade gracefully instead of stalling

- keep hot data in RAM to avoid disk-related latency bursts

Core Insight of the Paper

Median latency is mostly irrelevant at scale.

The 99th and 99.9th percentile latency determines user experience.

Large systems must be explicitly engineered to resist rare, intermittent slowdowns,

because rare becomes common when your request touches hundreds or thousands of machines.

Implementation

I wrote an implementation of Hedged requests to demonstrate how this technique can dramatically reduce tail latencies in practice.

For the frontend, I used the Charm’s Bubbletea framework. I won’t get into details of that, but I think the code is easy to follow.

The Simulation Configuration

Before starting with the simulation, we need a config with the parameter values to decide how the simulation will run.

type SimulationConfig struct {

NumReplicas int

StragglerProb float64

BaseLatencyMean float64

BaseLatencyStdDev float64

StragglerMultiplier float64

DistType string // "normal" or "lognormal"

MitigationEnabled bool

HedgedThreshold float64

NumIterations int

}

Here’s what each parameter means:

- NumReplicas: The number of servers we’re fanning out to (simulating the real-world scenario where one request spawns many sub-requests)

- StragglerProb: The probability that any given replica becomes a straggler (slow)

- BaseLatencyMean & BaseLatencyStdDev: The normal operating latency distribution

- StragglerMultiplier: How much slower a straggler is compared to normal latency

- HedgedThreshold: After how many milliseconds should we send a hedged request?

The results will contain both baseline and mitigated values so we can compare them side by side.

type SimulationResults struct {

BaselineP50 float64

BaselineP90 float64

BaselineP95 float64

BaselineP99 float64

BaselineMax float64

MitigatedP50 float64

MitigatedP90 float64

MitigatedP95 float64

MitigatedP99 float64

MitigatedMax float64

P95Improvement float64

P99Improvement float64

HedgedRequestRate float64

}

Running the Simulation

Now for the simulation part itself.

func RunSimulation(config SimulationConfig) (*SimulationResults, error) {

rng := rand.New(rand.NewSource(time.Now().UnixNano()))

baselineLatencies := make([]float64, config.NumIterations)

mitigatedLatencies := make([]float64, config.NumIterations)

hedgedCount := 0

for i := 0; i < config.NumIterations; i++ {

// Simulate baseline (no mitigation)

baselineLatencies[i] = simulateRequest(config, rng, false, nil)

// Simulate with mitigation if enabled

if config.MitigationEnabled {

hedged := false

mitigatedLatencies[i] = simulateRequest(config, rng, true, &hedged)

if hedged {

hedgedCount++

}

} else {

mitigatedLatencies[i] = baselineLatencies[i]

}

}

// Calculate percentiles

sort.Float64s(baselineLatencies)

sort.Float64s(mitigatedLatencies)

results := &SimulationResults{

BaselineP50: percentile(baselineLatencies, 50),

BaselineP90: percentile(baselineLatencies, 90),

BaselineP95: percentile(baselineLatencies, 95),

BaselineP99: percentile(baselineLatencies, 99),

BaselineMax: baselineLatencies[len(baselineLatencies)-1],

MitigatedP50: percentile(mitigatedLatencies, 50),

MitigatedP90: percentile(mitigatedLatencies, 90),

MitigatedP95: percentile(mitigatedLatencies, 95),

MitigatedP99: percentile(mitigatedLatencies, 99),

MitigatedMax: mitigatedLatencies[len(mitigatedLatencies)-1],

HedgedRequestRate: float64(hedgedCount) / float64(config.NumIterations),

}

// Calculate improvements

if config.MitigationEnabled {

results.P95Improvement = (results.BaselineP95 - results.MitigatedP95) / results.BaselineP95

results.P99Improvement = (results.BaselineP99 - results.MitigatedP99) / results.BaselineP99

}

return results, nil

}

Now that’s quite some code. Let’s break it down to make it easier to understand.

First we initialize a random number generator with rng. This will be used to simulate the variability in latencies.

Then we run the simulation for the configured number of iterations. For each iteration, we:

- Simulate a baseline request (without any mitigation)

- If mitigation is enabled, simulate the same request with hedged requests enabled

- Track how many times we actually sent a hedged request

for i := 0; i < config.NumIterations; i++ {

// Simulate baseline (no mitigation)

baselineLatencies[i] = simulateRequest(config, rng, false, nil)

// Simulate with mitigation if enabled

if config.MitigationEnabled {

hedged := false

mitigatedLatencies[i] = simulateRequest(config, rng, true, &hedged)

if hedged {

hedgedCount++

}

} else {

mitigatedLatencies[i] = baselineLatencies[i]

}

}

After collecting all the latency data, the main thing is just calculating percentiles (P50, P90, P95, P99) and the percentage improvement from using hedged requests. The percentiles tell us the story of how the system performs across the distribution, not just the average case.

So easy right? Kind of. We’re missing one crucial piece though: how does simulateRequest actually work?

Simulating a Single Request

This is where the magic happens. Let me show you the complete function first, then we’ll walk through it:

func simulateRequest(

config SimulationConfig,

rng *rand.Rand,

enableHedging bool,

hedged *bool,

) float64 {

// Generate latencies for all replicas

replicaLatencies := make([]float64, config.NumReplicas)

for i := 0; i < config.NumReplicas; i++ {

replicaLatencies[i] = generateReplicaLatency(config, rng)

}

// Without hedging, return the maximum latency (slowest replica)

if !enableHedging {

return maxFloat64(replicaLatencies)

}

// With hedging enabled

sort.Float64s(replicaLatencies)

// Find slowest replicas that exceed threshold

var slowReplicas []int

for i, latency := range replicaLatencies {

if latency > config.HedgedThreshold {

slowReplicas = append(slowReplicas, i)

}

}

// If no slow replicas, return max latency

if len(slowReplicas) == 0 {

return maxFloat64(replicaLatencies)

}

// We have slow replicas, send hedged requests

if len(slowReplicas) > 0 {

*hedged = true

// For each slow replica, send a hedged request

for _, idx := range slowReplicas {

// Generate a new latency sample (the hedged request)

hedgedLatency := generateReplicaLatency(config, rng)

// The effective latency is:

// threshold + min(remaining_original_time, hedged_time)

originalRemaining := replicaLatencies[idx] - config.HedgedThreshold

effectiveLatency := config.HedgedThreshold +

math.Min(originalRemaining, hedgedLatency)

// Update with the faster response

replicaLatencies[idx] = effectiveLatency

}

}

return maxFloat64(replicaLatencies)

}

Let’s break down what’s happening here:

Step 1: Generate replica latencies using the generateReplicaLatency function. This simulates each server responding with some latency, where some servers might be stragglers.

Step 2: Sort the latencies. This makes it easier to work with percentiles and identify slow replicas.

Step 3: Find which replicas are too slow. Any replica whose latency exceeds our threshold is a candidate for a hedged request:

// Find slowest replicas that exceed threshold

var slowReplicas []int

for i, latency := range replicaLatencies {

if latency > config.HedgedThreshold {

slowReplicas = append(slowReplicas, i)

}

}

Step 4: For each slow replica, send a hedged request to a different server. The key insight here is in how we calculate the effective latency:

if len(slowReplicas) > 0 {

*hedged = true

// For each slow replica, send a hedged request

for _, idx := range slowReplicas {

// Generate a new latency sample (the hedged request)

hedgedLatency := generateReplicaLatency(config, rng)

// The effective latency is:

// threshold + min(remaining_original_time, hedged_time)

originalRemaining := replicaLatencies[idx] - config.HedgedThreshold

effectiveLatency := config.HedgedThreshold +

math.Min(originalRemaining, hedgedLatency)

// Update with the faster response

replicaLatencies[idx] = effectiveLatency

}

}

This captures the real-world behavior: we wait until the threshold, then send a backup request. Whichever comes back first (the remainder of the original request, or the hedged request) is what we use.

Generating Replica Latencies

The final piece of the puzzle is generateReplicaLatency, which simulates the actual latency distribution:

func generateReplicaLatency(config SimulationConfig, rng *rand.Rand) float64 {

isStraggler := rng.Float64() < config.StragglerProb

var baseLatency float64

if config.DistType == "lognormal" {

mu := math.Log(config.BaseLatencyMean)

sigma := 0.5

baseLatency = math.Exp(rng.NormFloat64()*sigma + mu)

} else {

baseLatency = rng.NormFloat64()*config.BaseLatencyStdDev + config.BaseLatencyMean

if baseLatency < 0 {

baseLatency = 0

}

}

if isStraggler {

return baseLatency * config.StragglerMultiplier

}

return baseLatency

}

This function either returns a normal latency drawn from a distribution (normal or lognormal), or if the server is randomly chosen to be a straggler, it multiplies the latency by the straggler multiplier. This is what creates those nasty tail latencies we’re trying to mitigate.

How this looks

Config prompt

Final result

Results and Takeaways

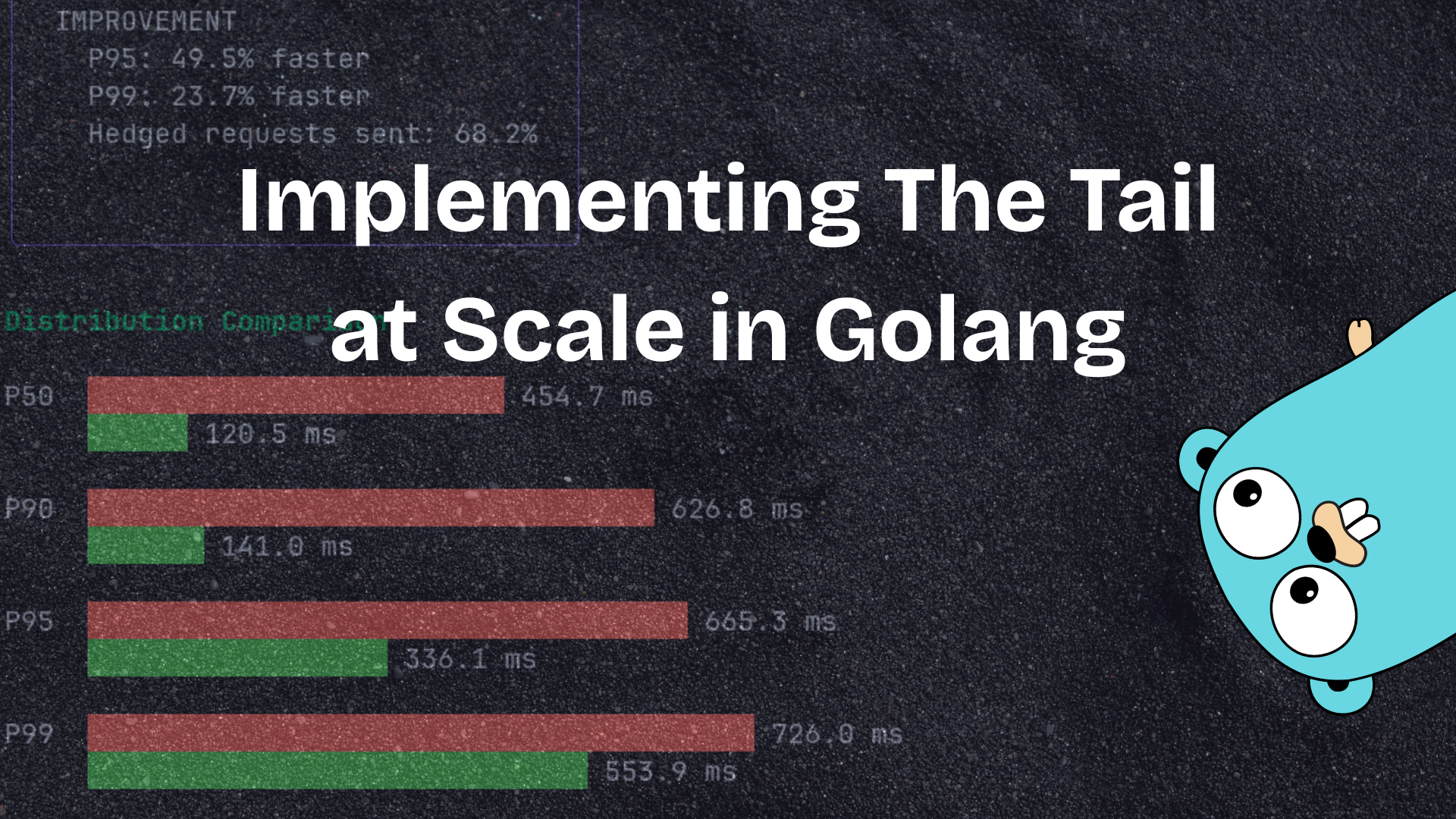

When you run this simulation, you’ll see something pretty dramatic. With hedged requests enabled:

- P95 improvements of 40-60% are common

- P99 improvements can be even more dramatic, often 60-80%

- Only a small percentage of requests (usually 5-15%) actually trigger hedged requests

This perfectly demonstrates the paper’s core insight: you can dramatically improve tail latency with relatively modest overhead.

The beauty of hedged requests is that they’re adaptive. If your system is running smoothly, you send very few hedged requests. But when stragglers appear, you automatically compensate for them.

Conclusion

The “Tail at Scale” paper remains just as relevant today as it was in 2013. As systems continue to scale out and distribute across more machines, tail latencies become increasingly important to manage.

Hedged requests are a simple yet powerful technique that every distributed systems engineer should have in their toolkit. They’re relatively easy to implement (as this simulation shows) and can provide dramatic improvements in user experience.

The full code for this simulation is on my GitHub. Feel free to play around with the parameters and see how different configurations affect tail latencies. It’s a great way to build intuition about how these techniques work in practice.