Recently, I read the the Google Bigtable paper, and what a fun read it was.

And I asked myself, how much of it can I fit in a single go file, with no external dependencies whatsoever, and it turns out, quite a lot. And that’s what this blog post is about. My implementation of this famous paper.

1. What Is Bigtable?

Bigtable is a distributed storage system designed to scale to petabytes of data across thousands of commodity servers. Despite being called a “table,” it is not a relational database.

I mean sure it does resemble a database, but it does something different, and it does it really well. It provides clients with a simple data model that supports dynamiccontrol over data layout and format, and allow clients to reason about the locality properties of the data represented in the underlying storage.

It is a sparse, distributed, persistent, multidimensional sorted map. Very big words right? Don’t be intimidated. It basically means you have sorted dictionary(I’m assuming you’re familiar with python a bit) as your primary data structure.

If this still seems daunting to look at, if translated to golang, this is how it would look like:

type RowKey []byte

func (r RowKey) String() string { return string(r) }

func (r RowKey) Compare(other RowKey) int {

return bytes.Compare(r, other)

}

type Column struct {

Family string

Qualifier string

}

func (c Column) String() string {

return c.Family + ":" + c.Qualifier

}

// This is the "big" table

type Cell struct {

Row RowKey

Col Column

Timestamp Timestamp

Value []byte

Deleted bool

}

But what was the need of BigTable?

When data you have to store gets to a humongous size, you need certain things in check:

- Wide applicability

- Scalability

- High Performance(of course)

- High availability!!!

BigTable solved for these problems, BigTable was used for a variety of workloads, from latency sensitive data serving to heavy throughput batch processing. Every piece of data is indexed by three coordinates:

(row key, column key, timestamp) → value

- Row keys are arbitrary byte strings, sorted lexicographically. All reads and writes to a single row are atomic.

- Column keys are grouped into column families (e.g.,

anchor,contents). Within a family, column qualifiers can be anything. - Timestamps allow multiple versions of a value to coexist. The system can be configured to keep the latest N versions or all versions within a time window.

The data model gives users enormous flexibility. Google’s original use cases included the web index (storing crawled HTML with timestamps), Google Analytics, Google Earth, and Gmail.

Pretty simple right? Now let’s discuss what do each field in the Cell struct actually mean.

2. Constants and Configuration

Before we get into the fun stuff, let’s talk about the boring-but-important numbers that control how the whole system behaves. Think of these as the dials you’d turn if you were deploying this in production.

const (

DefaultMemtableMaxSize = 4 * 1024 * 1024

DefaultMajorCompactionThreshold = 5

MetadataTableName = "METADATA"

MaxTabletsPerServer = 1000

ChubbyLeaseDuration = 10 * time.Second

...

)

DefaultMemtableMaxSize(4 MB): Once an in-memory write buffer (the memtable) reaches this size, it is frozen and flushed to disk as an SSTable. In production Bigtable this is configurable per table.DefaultMajorCompactionThreshold(5): After 5 SSTables accumulate for a tablet, a major compaction is triggered to merge them into one, reclaiming space from deleted data.MetadataTableName: The special internalMETADATAtable stores the locations of all user tablets. It is managed by Bigtable itself, not by users.MaxTabletsPerServer(1000): A safety cap on how many tablets one server can hold. Real servers handle tablet counts based on memory and I/O capacity.ChubbyLeaseDuration(10s): How long a Chubby session remains valid between heartbeats. If a tablet server fails to renew within this window, the master declares it dead.LatestTimestamp: A sentinel value (MaxInt64) used when searching for the newest version of a cell. By sorting timestamps in descending order, the newest version always comes first.

3. Core Data Types

This section defines the fundamental vocabulary of the system, the building blocks every other component uses.

Timestamp

type Timestamp int64

func Now() Timestamp {

return Timestamp(time.Now().UnixMicro())

}

Timestamps are microsecond-precision Unix timestamps stored as int64. The paper states that clients can assign their own timestamps for controlled versioning, or let Bigtable assign them automatically. Now() is the automatic assignment path.

RowKey

type RowKey []byte

func (r RowKey) Compare(other RowKey) int {

return bytes.Compare(r, other)

}

Row keys are raw byte slices. The entire Bigtable data model hinges on lexicographic ordering of row keys, this is what makes range scans efficient. A famous design pattern from the paper is reversing domain names (com.google instead of google.com) so that pages from the same domain cluster together on disk.

Column and ColumnFamily

type Column struct {

Family string

Qualifier string

}

A column is identified by two parts separated by a colon: family:qualifier. The family (anchor, contents, language) is defined at table-creation time and controls compression, versioning policy, and memory residency. The qualifier is dynamic, it can be anything and is not declared in advance. This is what makes Bigtable “sparse”: a row only stores the columns it actually has values for.

Cell

type Cell struct {

Row RowKey

Col Column

Timestamp Timestamp

Value []byte

Deleted bool

}

A Cell is one versioned value at a specific (row, column, timestamp) coordinate. The Deleted flag makes it a tombstone , a marker that says “this cell was deleted.” Tombstones are how deletions propagate through the system before a major compaction permanently removes the data.

CellKey and CompareCellKeys

type CellKey struct {

Row, Family, Qualifier string

Timestamp Timestamp

}

func CompareCellKeys(a, b CellKey) int {

// row asc → family asc → qualifier asc → timestamp desc

}

CellKey is the sort key used throughout the system, in the memtable, in SSTables, and during merge operations. The critical detail is that timestamps are sorted descending: newest versions come first. This means a simple forward scan naturally yields the most recent version first, which is what most reads want.

Mutation

type Mutation struct {

Type MutationType

Col Column

Timestamp Timestamp

Value []byte

}

Mutations represent write operations. There are four types: MutationSet (write a value), MutationDelete (delete a cell), MutationDeleteRow (delete all cells in a row), and MutationDeleteFamily (delete all cells in a column family). Per-row atomicity means all mutations in one Write() call either all succeed or all fail.

RowRange

type RowRange struct {

Start RowKey // inclusive

End RowKey // exclusive; nil means unbounded

}

RowRange defines a half-open interval [Start, End) over row keys. This is the unit of work for scans. nil endpoints represent unbounded ranges, meaning “start of table” or “end of table.” Tablets are also described by RowRanges , a tablet server only accepts reads and writes for row keys within its assigned range.

4. Schema

type TableSchema struct {

Name string

ColumnFamilies map[string]*ColumnFamily

}

A TableSchema is the schema object created when a user calls CreateTable. In Bigtable, schema changes are lightweight, you can add or remove column families without touching the data. The ColumnFamily struct stores per-family tuning parameters:

type ColumnFamily struct {

Name string

MaxVersions int

TTL time.Duration

Compression string // "none", "snappy", "zlib"

BloomFilter bool

InMemory bool

}

MaxVersions: How many historical versions to keep. Once the limit is exceeded, old versions are garbage-collected during compaction.TTL: Time-to-live. Versions older than this duration are automatically deleted during compaction.Compression: SSTables for this family will be compressed using the named algorithm. Compression is per-family because some data (like HTML) compresses well while other data (like encrypted blobs) does not.InMemory: If true, all SSTables for this column family are kept in memory for faster reads. The paper uses this for theMETADATAtable’s location columns.

AddColumnFamily enforces uniqueness and sets default values. GetColumnFamily uses a read lock for concurrent access.

5. GFS : The Storage Foundation

type GFS struct {

baseDir string

mu sync.Mutex

files map[string]*GFSFile

}

In the real Bigtable, the Google File System (GFS) provides a reliable, replicated, distributed file system. GFS handles replication, fault tolerance, and large sequential I/O. Our implementation simulates GFS using the local filesystem under /tmp/bigtable_gfs.

The GFS struct tracks a registry of open files and delegates to standard os package operations. The key methods are:

Create(name): Creates a new file, ensuring all parent directories exist.Append(name, data): Opens the file in append mode and writes bytes atomically. This is the primary write pattern for the commit log.Read(name): Returns the entire file contents. In real GFS, reads can be streamed in chunks.Write(name, data): Atomically replaces a file’s content. This is used for SSTable creation: write the whole file at once, then make it visible.Register(name): Registers a file that already exists on disk (used during recovery).

The design of GFS is central to Bigtable’s architecture. Because GFS replicates data across machines, Bigtable does not need to implement its own replication. SSTables are immutable once written, which makes them trivially replicable and cacheable.

6. Chubby: The Lock Service

Chubby is a distributed lock service that Bigtable relies on for five critical functions:

- Master election: Only one master can hold the master lock at a time.

- Tablet server liveness: Each tablet server holds a lock; if the lock is lost, the master knows the server is dead.

- Root tablet location: Chubby stores the address of the root tablet, which is the entry point for the tablet location hierarchy.

- ACLs: Access control lists are stored as Chubby files.

- Schema bootstrap: The existence of a Bigtable cluster is anchored in a Chubby directory.

type Chubby struct {

nodes map[string]*ChubbyNode

sessions map[string]*ChubbySession

}

type ChubbyNode struct {

Path string

Content []byte

Lock string // session ID holding the lock

Watchers map[string]chan struct{}

}

Sessions and Leases

type ChubbySession struct {

id string

leaseExp time.Time

}

Every participant (master, each tablet server, each client) opens a Chubby session. Sessions have leases that must be periodically renewed via RenewLease(). If a lease expires, the session becomes invalid, any locks held by that session are released, and watchers are notified. This is how Bigtable detects server failures without an explicit heartbeat protocol.

Locks

func (c *Chubby) TryLock(path string, sess *ChubbySession) bool {

...

if node.Lock == "" {

node.Lock = sess.id

return true

}

return node.Lock == sess.id

}

Locks are exclusive. TryLock is non-blocking: it returns true if the lock was acquired, false if another session holds it. This is what the master uses for election: whichever process wins the lock first becomes the active master.

Watches

func (c *Chubby) Watch(path string, sess *ChubbySession) (<-chan struct{}, error)

Watches provide event notification. A watcher is notified when a node’s content changes or its lock is released. The master uses watches to detect when a tablet server’s lock node disappears (server died) and to monitor configuration changes.

Pre-created Paths

The constructor creates the standard Bigtable Chubby paths:

/bigtable/master-lock: The master election lock./bigtable/root-tablet-location: Stores where the root tablet lives./bigtable/servers: A directory where each tablet server creates its lock file./bigtable/acls: Access control lists.

7. Bloom Filter

type BloomFilter struct {

bits []uint64

numBits uint

numHash uint

}

Okay, this one is my favorite. A Bloom filter may sound fancy but it does exactly one thing: it tells you whether something is definitely not in a set, or probably is. That asymmetry is surprisingly powerful.

func (bf *BloomFilter) MightContain(key []byte) bool {

for i := uint(0); i < bf.numHash; i++ {

pos := bf.hash(key, i)

if bf.bits[pos/64]&(1<<(pos%64)) == 0 {

return false

}

}

return true

}

Why it matters for performance: Without Bloom filters, a read for a row that doesn’t exist in a given SSTable would require loading and scanning that SSTable’s index from disk. With a Bloom filter, the tablet server can skip the disk read entirely if MightContain returns false. For workloads with many “point reads” of non-existent keys, this can eliminate the majority of SSTable I/O.

The filter uses CRC32 hashing with a seed per hash function. The number of bits and hash functions is computed from the expected item count and desired false positive rate using the standard Bloom filter formulas.

8. Memtable: The In-Memory Write Buffer

type Memtable struct {

entries []MemtableEntry // sorted slice of CellKey -> Cell

size int64

frozen bool

seqNo int64

}

The memtable is the first place every write lands. It is an in-memory sorted buffer maintained in CellKey order. When the memtable reaches the size threshold (DefaultMemtableMaxSize), it is frozen and flushed to GFS as an immutable SSTable. A new, empty memtable takes its place.

Sorted Insertion

func (m *Memtable) Insert(cell *Cell) error {

...

idx := sort.Search(len(m.entries), func(i int) bool {

return CompareCellKeys(m.entries[i].key, key) >= 0

})

// Insert at idx, shifting right

m.entries = append(m.entries, MemtableEntry{})

copy(m.entries[idx+1:], m.entries[idx:])

m.entries[idx] = entry

...

}

Binary search (sort.Search) finds the insertion point in O(log n) time. The slice is then shifted to make room: O(n) in the worst case, but acceptable for in-memory operations. In a production system, a skip list or balanced BST (like a red-black tree) would give O(log n) insertion and avoid the copy. The paper mentions that the original Bigtable used a skip list.

Get and Scan

Get(row, col, maxVersions) uses a binary search to find the starting position (using LatestTimestamp as a sentinel to land before all versions of the key) then walks forward collecting versions.

Scan(rng, families) similarly seeks to rng.Start and walks forward, skipping cells in families not in the filter set.

Freeze

func (m *Memtable) Freeze() {

m.mu.Lock()

m.frozen = true

m.mu.Unlock()

}

Freezing a memtable is a lightweight operation: it just sets a flag. After freezing, the memtable becomes read-only. Write attempts return an error. The frozen memtable is added to the immutable slice on the tablet and remains readable while it is being written to disk.

Iterator

type MemtableIterator struct {

m *Memtable

idx int

}

The iterator provides a cursor over the sorted entries, used during SSTable creation (the writer walks the memtable in order to produce a sorted SSTable).

9. Commit Log: The Write-Ahead Log

type CommitLog struct {

gfs *GFS

path string

seqNo int64

encoder *json.Encoder

file *os.File

}

The commit log is the durability guarantee of the system. Before any mutation is applied to the memtable, it must be durably written to the commit log on GFS. If the tablet server crashes, the log can be replayed to reconstruct the memtable.

One Log Per Server (Not Per Tablet)

Here’s a decision that seems weird at first: instead of each tablet keeping its own log, the entire server shares one. Sounds messy, right? Turns out it’s actually smarter. This dramatically reduces the number of concurrent GFS writes (GFS writes are expensive). The tradeoff is that recovery becomes more complex: when a server fails and its tablets are reassigned to different servers, each new server must sort through the log to find entries relevant to its tablets.

func (cl *CommitLog) Append(tabletID string, cell *Cell) (int64, error) {

cl.mu.Lock()

defer cl.mu.Unlock()

cl.seqNo++

rec := &LogRecord{SeqNo: cl.seqNo, TabletID: tabletID, Cell: cell}

return cl.seqNo, cl.encoder.Encode(rec)

}

Each record is tagged with its tabletID so that during recovery, a server can filter for only the tablets it owns.

Recovery

func (cl *CommitLog) ReadFrom(minSeq int64) ([]*LogRecord, error) {

// JSON-decode all records from disk, filter by seqNo >= minSeq

}

ReadFrom replays the log from a given sequence number. Tablet.Recover() calls this and re-inserts the relevant cells into a fresh memtable. The minSeq parameter allows the system to skip log entries that were already flushed to SSTables before the crash.

10. SSTable: Immutable On-Disk Storage

Once the memtable is full and frozen, it needs to go somewhere permanent. That’s where SSTables come in, immutable files that sit on GFS and never change once written. Immutability sounds like a constraint, but it’s actually what makes everything else easier: caching, replication, concurrent reads, all of it.

File Format

The SSTable binary format consists of four sections:

[ Data Blocks ][ Index Block ][ Bloom Filter ][ Footer (20 bytes) ]

- Data Blocks: Fixed-size blocks of JSON-encoded cells, sorted by

CellKey. Each block is up to 64 KB. - Index Block: A JSON-encoded array of

(blockOffset, firstKey)pairs, one entry per data block. This allows binary search to find the block containing a target key. - Bloom Filter: A JSON-encoded bloom filter covering all

(row, family, qualifier)triples in the file. - Footer: Two

int64values (offsets to the index and bloom filter) and a magic number (0xB16B00B5) for validation.

SSTableWriter

type SSTableWriter struct {

buf bytes.Buffer

index SSTableIndex

bloom *BloomFilter

blockCells []*Cell

maxBlockSize int

}

The writer accumulates cells in blockCells. When the block reaches maxBlockSize, flushBlock() is called:

func (w *SSTableWriter) flushBlock() {

offset := int64(w.buf.Len())

w.index.BlockOffsets = append(w.index.BlockOffsets, offset)

w.index.FirstKeys = append(w.index.FirstKeys, w.blockCells[0].Key())

binary.Write(&w.buf, binary.LittleEndian, uint32(len(w.blockCells)))

for _, c := range w.blockCells {

enc.Encode(c)

}

}

The first key of each block is saved in the index so that readers can binary-search the index to skip directly to the right block.

Finish() flushes the last block, writes the index and bloom filter, writes the footer, then atomically writes the entire buffer to GFS.

SSTableReader

type SSTableReader struct {

path string

gfs *GFS

data []byte

index SSTableIndex

bloom *BloomFilter

loaded bool

}

The reader is lazy, it only loads data from GFS on the first access (load()). This avoids I/O for SSTables that are never read.

Get path:

- Check bloom filter. If

MightContainreturns false, return immediately (no I/O). - Binary-search the index for the block likely containing the key.

- Decode only that block from

data. - Walk the decoded cells looking for matches.

Scan path: Walk all blocks in order, filtering by row range and column families.

11. Tablet: A Contiguous Row Range

A tablet is the fundamental unit of distribution and load balancing in Bigtable. Each tablet covers a contiguous range of rows [StartKey, EndKey) in one table.

type Tablet struct {

ID TabletID

Schema *TableSchema

state TabletState

memtable *Memtable

immutable []*Memtable // frozen, awaiting flush

sstables []*SSTableReader // newest first

blockCache *BlockCache

scanCache *ScanCache

log *CommitLog

gfs *GFS

}

The Merged Read View

The key insight of the tablet’s read path is that at any moment, data for a row may exist in:

- The active memtable (most recent writes)

- Zero or more frozen (immutable) memtables (being flushed)

- Zero or more SSTables on GFS (previously flushed data)

A correct read must return the union of all these sources, sorted by timestamp descending:

func (t *Tablet) Get(row RowKey, col Column, maxVersions int) ([]*Cell, error) {

allCells = append(allCells, mem.Get(row, col, maxVersions)...)

for _, im := range immutable {

allCells = append(allCells, im.Get(row, col, maxVersions)...)

}

for _, sst := range sstables {

cells, _ := sst.Get(row, col, maxVersions)

allCells = append(allCells, cells...)

}

return mergeCells(allCells, maxVersions), nil

}

mergeCells

func mergeCells(cells []*Cell, maxVersions int) []*Cell {

sort.Slice(cells, ...)

// Walk in order, applying tombstones, enforcing version limits

}

mergeCells handles three concerns:

- Deduplication: The same key can appear in multiple sources; the memtable’s version wins.

- Tombstones: If a

Deletedcell is encountered, all subsequent versions of that(row),(row, family), or(row, family, qualifier)are suppressed. - Version limits: Only the first

maxVersionsnon-deleted cells per(row, family, qualifier)group are returned.

Minor Compaction

func (t *Tablet) MinorCompaction() error {

// 1. Freeze active memtable, swap in a new empty one

t.memtable.Freeze()

frozen := t.memtable

t.memtable = NewMemtable(newSeq)

t.immutable = append(t.immutable, frozen)

// 2. Write frozen memtable to a new SSTable

writer := NewSSTableWriter(t.gfs, sstPath)

for _, e := range frozen.entries {

writer.Add(e.cell)

}

writer.Finish()

// 3. Register the new SSTable as the newest

t.sstables = append([]*SSTableReader{reader}, t.sstables...)

}

Minor compaction converts the frozen memtable into an SSTable. It is triggered automatically when the memtable exceeds DefaultMemtableMaxSize. The frozen memtable stays readable until the SSTable is confirmed written, ensuring no data is lost.

Major Compaction

func (t *Tablet) MajorCompaction() error {

// 1. Read all cells from all existing SSTables

// 2. Merge them (mergeCells removes tombstones permanently)

// 3. Write a single new SSTable

// 4. Replace all old SSTables with the new one

}

Major compaction is triggered when more than DefaultMajorCompactionThreshold SSTables exist. It serves two purposes:

- Reclaims storage: Tombstones are only permanently removed during major compaction. Until then, they must be carried through minor compactions.

- Improves read performance: Each additional SSTable is one more source the read path must check. Reducing to a single SSTable minimizes I/O.

The compacting atomic flag prevents concurrent major compactions on the same tablet.

Tablet Split

func (t *Tablet) Split() (*Tablet, *Tablet, error) {

midKey := RowKey(entries[len(entries)/2].key.Row)

leftID := TabletID{..., EndKey: midKey}

rightID := TabletID{..., StartKey: midKey}

return NewTablet(leftID, ...), NewTablet(rightID, ...), nil

}

When a tablet grows too large (not wired up in this demo but structurally complete), it is split at the median key. The master is notified, which updates the METADATA table and reassigns one of the two new tablets. Splits are always initiated by the tablet server (which knows the data), while the master coordinates the resulting reassignment.

Tablet States

type TabletState int

const (

TabletLoading TabletState = iota

TabletServing

TabletCompacting

TabletUnloading

)

State transitions prevent races: a tablet in TabletCompacting state rejects new compaction requests; one in TabletUnloading is being prepared for transfer to another server.

12. Caches: Block Cache and Scan Cache

Two reads of the same row shouldn’t cost the same as two reads of completely different rows. That’s the whole motivation for caching here. Both caches use a simple FIFO eviction policy (a production system would use LRU):

type BlockCache struct {

data map[string][]*Cell

order []string

maxSize int

}

type ScanCache struct {

data map[string][]*Cell

order []string

maxSize int

}

Block Cache

The block cache stores decoded SSTable blocks. Without it, reading the same block twice (e.g., two reads of rows that fall in the same SSTable block) would require two disk reads and two JSON decodes. The block cache is especially valuable for hot row ranges.

Scan Cache

The scan cache stores the final merged results of Get calls, keyed by "get:{row}:{col}". This is a higher-level cache: if the same (row, column) is read multiple times without any intervening writes, the second read is served directly from the cache without touching the memtable or any SSTable.

The scan cache is invalidated after writes (to ensure read-your-writes consistency) and after minor compactions (because the memtable contents changed). The Clear() method wipes the entire scan cache when a compaction completes.

13. Tablet Server

type TabletServer struct {

ID string

chubby *Chubby

session *ChubbySession

lockPath string

gfs *GFS

tablets map[string]*Tablet

commitLog *CommitLog

schemas map[string]*TableSchema

}

The tablet server is the workhorse of the system. It holds a set of tablets, receives direct read/write requests from clients, and manages background compaction.

Startup and Liveness

ts.lockPath = "/bigtable/servers/" + id

chubby.TryLock(ts.lockPath, ts.session)

On startup, every tablet server creates a node in Chubby’s /bigtable/servers/ directory and acquires an exclusive lock on it. As long as this lock is held, the master knows the server is alive. The lock is maintained by the heartbeatLoop goroutine, which calls RenewLease every 2 seconds.

Background Goroutines

Three goroutines run continuously:

heartbeatLoop: Renews the Chubby session lease to maintain liveness.minorCompactionLoop: Polls all tablets for pending flush requests (via theminorFlushChchannel) and callsMinorCompaction().majorCompactionLoop: Polls all tablets for pending major compaction requests (viamajorCompactCh) and callsMajorCompaction().

Using channels for triggering (rather than polling size directly) means compaction is triggered immediately when thresholds are crossed, while the background loops add no overhead when nothing needs to be done.

The Write Path

func (ts *TabletServer) Write(tabletStr string, row RowKey, mutations []Mutation) error {

// 1. Verify session (ACL check via Chubby)

if !ts.session.IsValid() { return err }

for _, m := range mutations {

cell := &Cell{...}

// 2. Write to commit log (WAL), MUST persist before memtable

ts.commitLog.Append(tabletStr, cell)

// 3. Insert into memtable

t.Apply(cell)

}

// 4. Invalidate scan cache for written rows

}

The ordering is critical: the WAL write must complete before the memtable write. If the server crashes after the WAL write but before the memtable write, recovery will replay the WAL and reconstruct the memtable. If the crash happened before the WAL write, neither the WAL nor the memtable has the data, but the client never received an acknowledgment, so it will retry.

The Read Path

func (ts *TabletServer) Read(tabletStr string, row RowKey, col Column, maxVersions int) ([]*Cell, error) {

t, err := ts.getTablet(tabletStr)

return t.Get(row, col, maxVersions)

}

Reads go directly to the tablet’s Get() method, which implements the merged view described in the Tablet section. Clients communicate directly with tablet servers, the master is not involved in the read path at all.

Atomic Read-Modify-Write

func (ts *TabletServer) ReadModifyWrite(tabletStr string, row RowKey, ops []ReadModifyWrite) error {

t.memMu.Lock() // hold the tablet's write lock for atomicity

defer t.memMu.Unlock()

for _, op := range ops {

existing, _ := t.Get(row, op.Col, 1)

// Compute new value (increment or append)

// Write to WAL and memtable

}

}

Atomicity is achieved by holding the tablet’s memtable lock for the entire read-compute-write operation. This is a coarse-grained lock, but it’s correct: no other write can interleave with this operation. The paper describes a similar atomic CheckAndMutate operation for conditional writes.

14. Master Server

type Master struct {

chubby *Chubby

servers map[string]*TabletServer

schemas map[string]*TableSchema

assignments map[string]*TabletAssignment

unassigned []TabletID

}

The master is kind of like a manager who does zero actual work but keeps the whole team from falling apart. It never touches your data directly , clients never talk to it for reads or writes, but without it, nobody would know where anything lives. These are the operation master does:

- Tablet assignment: Tracking which tablet server owns which tablet.

- Server failure detection: Using Chubby watches to detect dead servers and reclaim their tablets.

- Load balancing: Moving tablets from overloaded servers to underloaded ones.

- Table creation: Creating schemas and initializing the first tablet.

Master Election

func (m *Master) Elect() error {

if !m.chubby.TryLock("/bigtable/master-lock", m.session) {

return errors.New("another master is already running")

}

m.isMaster = true

}

At most one master is active at any time, enforced by the Chubby lock. If the active master dies, the lock is released and a standby master can acquire it.

Server Monitoring

func (m *Master) checkServerLiveness() {

for id := range m.servers {

lockPath := "/bigtable/servers/" + id

if !m.chubby.IsLockHeld(lockPath) {

// Server is dead: reclaim all its tablets

for tabletStr, a := range m.assignments {

if a.ServerID == id {

m.unassigned = append(m.unassigned, a.TabletID)

delete(m.assignments, tabletStr)

}

}

delete(m.servers, id)

}

}

m.assignTablets()

}

Every 5 seconds, the master checks all known server lock paths in Chubby. If a lock is no longer held (the server died or its lease expired), the master marks all of that server’s tablets as unassigned and calls assignTablets() to redistribute them.

Tablet Assignment

func (m *Master) assignTablets() {

for _, tabletID := range m.unassigned {

// Find server with minimum current tablet count

// Register schema on that server, call ts.LoadTablet()

}

}

Assignment uses a greedy minimum-load heuristic: always assign to the server with the fewest tablets. A production system would factor in disk usage, memory pressure, and I/O load.

Load Balancing

func (m *Master) rebalance() {

// Find most-loaded and least-loaded servers

// If difference > 1, move one tablet from max to min

}

The rebalancer runs every 30 seconds and moves one tablet per cycle from the most-loaded server to the least-loaded. Moving tablets gracefully requires UnloadTablet (which flushes the memtable) followed by LoadTablet (which recovers from the log).

Table Creation

func (m *Master) CreateTable(schema *TableSchema) error {

m.schemas[schema.Name] = schema

initialTablet := TabletID{Table: schema.Name, StartKey: nil, EndKey: nil}

m.unassigned = append(m.unassigned, initialTablet)

m.assignTablets()

}

A new table starts with exactly one tablet covering the entire row key space [nil, nil). As data accumulates, tablets are split by the tablet servers. This is the standard “start with one shard, split as you grow” approach used by many distributed databases.

15. Tablet Location Hierarchy

Every read and write needs to find the right tablet server first. Do that naively and you’re adding a network round trip to every single operation. Bigtable’s solution is a three-level hierarchy that can locate any of ~34 billion tablets in just three hops, and in practice, usually zero, thanks to client-side caching.

Finding the right tablet server for a given (table, row) pair is a three-level lookup, a B+-tree-like hierarchy that can address up to ~2^34 tablets with just three network round trips.

Level 0: Chubby file at /bigtable/root-tablet-location

└── Contains address of ROOT tablet

Level 1: ROOT tablet (part of METADATA table, never split)

└── Contains locations of all other METADATA tablets

Level 2: METADATA tablets

└── Contains locations of all user tablets

The client-side cache makes this hierarchy efficient in practice:

type TabletLocationCache struct {

cache map[string]TabletLocation

}

type TabletLocation struct {

ServerID string

TabletStr string

ExpiresAt time.Time

}

Cache entries have a 30-second TTL. On a cache hit, the client contacts the tablet server directly, zero overhead. On a miss or a stale entry (tablet moved), the client re-traverses the hierarchy.

func (c *Client) findTabletServer(table string, row RowKey) (*TabletServer, string, error) {

if loc, ok := c.locCache.Get(table, row); ok {

ts, err := c.master.GetTabletServer(loc.TabletStr)

if err == nil {

return ts, loc.TabletStr, nil

}

c.locCache.Invalidate(table, row)

}

// Re-lookup via METADATA hierarchy (simplified: ask master directly)

ts, tabletStr, err := c.master.FindTablet(table, row)

c.locCache.Put(table, row, TabletLocation{TabletStr: tabletStr, ...})

return ts, tabletStr, nil

}

The paper notes that the client library prefetches tablet locations to further reduce latency. Our implementation includes the cache invalidation path: when a write fails (suggesting the tablet moved), the cache entry is invalidated before retrying.

16. Client Library

The client library is the public API of Bigtable. It hides all the complexity of location lookup, retry logic, and mutation encoding behind a clean interface.

Put, Get, Delete

func (c *Client) Put(table string, row RowKey, col Column, value []byte) error

func (c *Client) Get(table string, row RowKey, col Column) (*Cell, error)

func (c *Client) Delete(table string, row RowKey, col Column) error

These are the basic CRUD operations. Put creates a MutationSet; Delete creates a MutationDelete (tombstone). Get calls GetVersions with maxVersions=1 and returns the first result.

GetVersions

func (c *Client) GetVersions(table string, row RowKey, col Column, maxVersions int) ([]*Cell, error)

Returns up to maxVersions historical versions, newest first. This is a key differentiator from traditional databases, Bigtable natively supports historical reads without needing a separate audit log.

Scan

func (c *Client) Scan(table string, startRow, endRow RowKey, families []string, maxVersions int) ([]*Cell, error)

Scans a row range. In a real multi-tablet deployment, the scan would need to contact multiple tablet servers as it crosses tablet boundaries. This implementation handles the common single-tablet case; the multi-tablet case would require iterating FindTablet as the scan progresses.

BatchWrite

func (c *Client) BatchWrite(table string, row RowKey, mutations []Mutation) error

Applies multiple mutations to a single row in one call. Because Bigtable guarantees per-row atomicity, all mutations in a batch either all succeed or all fail. This is important for maintaining consistency within a row (e.g., updating multiple columns of a user record atomically).

Increment and Append

func (c *Client) Increment(table string, row RowKey, col Column, delta int64) error

func (c *Client) Append(table string, row RowKey, col Column, data []byte) error

These are higher-level operations built on top of ReadModifyWrite. Increment reads the current integer value, adds delta, and writes back. Append reads the current byte slice and appends data. Both are atomic because ReadModifyWrite holds the tablet’s write lock.

17. Cluster Bootstrap

type Cluster struct {

Chubby *Chubby

GFS *GFS

Master *Master

TabletServers []*TabletServer

}

func NewCluster(numServers int) (*Cluster, error) {

gfs := NewGFS(GFSBaseDir)

chubby := NewChubby()

master := NewMaster(chubby, gfs)

master.Elect()

// Start N tablet servers

// Register each with the master

master.Start()

return cluster, nil

}

NewCluster is the top-level constructor that bootstraps the entire system. It wires together all components in the correct order:

- GFS first: All other components need storage.

- Chubby next: Master election and server registration depend on it.

- Master election: The master acquires its Chubby lock before doing anything else.

- Tablet servers: Each opens a session, acquires its lock, and starts background goroutines.

- Master starts: Now that it has servers registered, the master begins monitoring and assignment loops.

- Root tablet location published: The Chubby node is updated so clients can begin resolving locations.

Cluster.CreateTable is a convenience method that creates a TableSchema, registers column families, and calls Master.CreateTable.

Cluster.Stop gracefully shuts down all servers and the master, releasing locks in the process.

18. The Demo

Okay enough theory. Let’s actually run the thing.

Step 1–2: Cluster Boot and Table Creation

cluster, _ := NewCluster(3)

cluster.CreateTable("webtable",

&ColumnFamily{Name: "anchor", MaxVersions: 5},

&ColumnFamily{Name: "contents", MaxVersions: 3, Compression: "zlib"},

&ColumnFamily{Name: "language", MaxVersions: 1},

)

We boot a 3-server cluster and create a webtable, the same example Google uses in the paper, which is a nice full-circle moment. The table has three column families: anchor for link anchor text, contents for the actual page HTML, and language. Row keys are reversed domain names (com.google, com.cnn.www) so that pages from the same domain end up physically next to each other on disk. This significantly makes it faster.

Step 3–4: Writes and Reads

Nothing fancy here, just a basic put followed by a get to confirm the write path and read path actually talk to each other correctly. If this works, the plumbing is good.

Step 5: Multi-Version Reads

client.PutWithTimestamp("webtable", row, col, value, t0)

client.PutWithTimestamp("webtable", row, col, value, t1)

client.PutWithTimestamp("webtable", row, col, value, t2)

versions, _ := client.GetVersions("webtable", row, col, 3)

This is one of my favorite parts of Bigtable. We write the same cell three times with different timestamps, then ask for all three versions back. They come out newest-first. This is exactly how the web crawl use case works in production, every time Google re-crawls a page, it doesn’t overwrite the old content, it just writes a new version. You can always go back and ask “what did this page look like six months ago?”

Step 6: Range Scan

cells, _ := client.Scan("webtable", RowKey("com.a"), RowKey("com.z"), nil, 1)

One line, but a lot happening under the hood. This scans every row between com.a and com.z. which, because of our reversed domain name trick, means every .com domain. The lexicographic ordering does all the heavy lifting here; this is not filtering per se, just exploiting how the data is laid out.

Step 7–8: Atomic Counter and Append

client.Increment("usertable", userRow, counterCol, 1) // 5 times

client.Append("usertable", userRow, logCol, []byte("|search"))

Both of these go through ReadModifyWrite, which holds the tablet’s write lock for the entire read-compute-write cycle. That’s what makes them atomic. Increment is exactly what you’d use for page view counts. Append is perfect for activity streams, every action just gets tacked onto the end of a log column.

Step 9: Deletion

client.Delete("webtable", row, col)

Looks simple, but this doesn’t actually delete anything yet. It writes a tombstone, a marker that says “this cell is gone.” The data physically disappears only when the next major compaction rolls around and merges everything together. Until then, the read path just sees the tombstone and skips over the old versions. It’s a bit like marking an email as deleted without emptying the trash.

Step 10: Compaction Under Load

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

client.Put("webtable", randomRow, col, value)

}

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

We hammer the table with 1000 writes to push the memtable over its 4MB threshold and trigger the background minor compaction loop. After the sleep, peek inside /tmp/bigtable_gfs/sstables/, you’ll actually see the SSTable files sitting on disk. That’s real data, written by the system we just built.

Step 11: Batch Write

server.Write(tabletStr, row, []Mutation{

{Col: Column{"profile", "name"}, Value: []byte("Alice")},

{Col: Column{"profile", "email"}, Value: []byte("alice@example.com")},

{Col: Column{"activity", "pageviews"}, Value: []byte("0")},

})

Three columns, one call, one atomic operation. Either all three land or none of them do. This is per-row atomicity in action, if you’re creating a user record and the server dies halfway through, you won’t end up with a row that has a name but no email address.

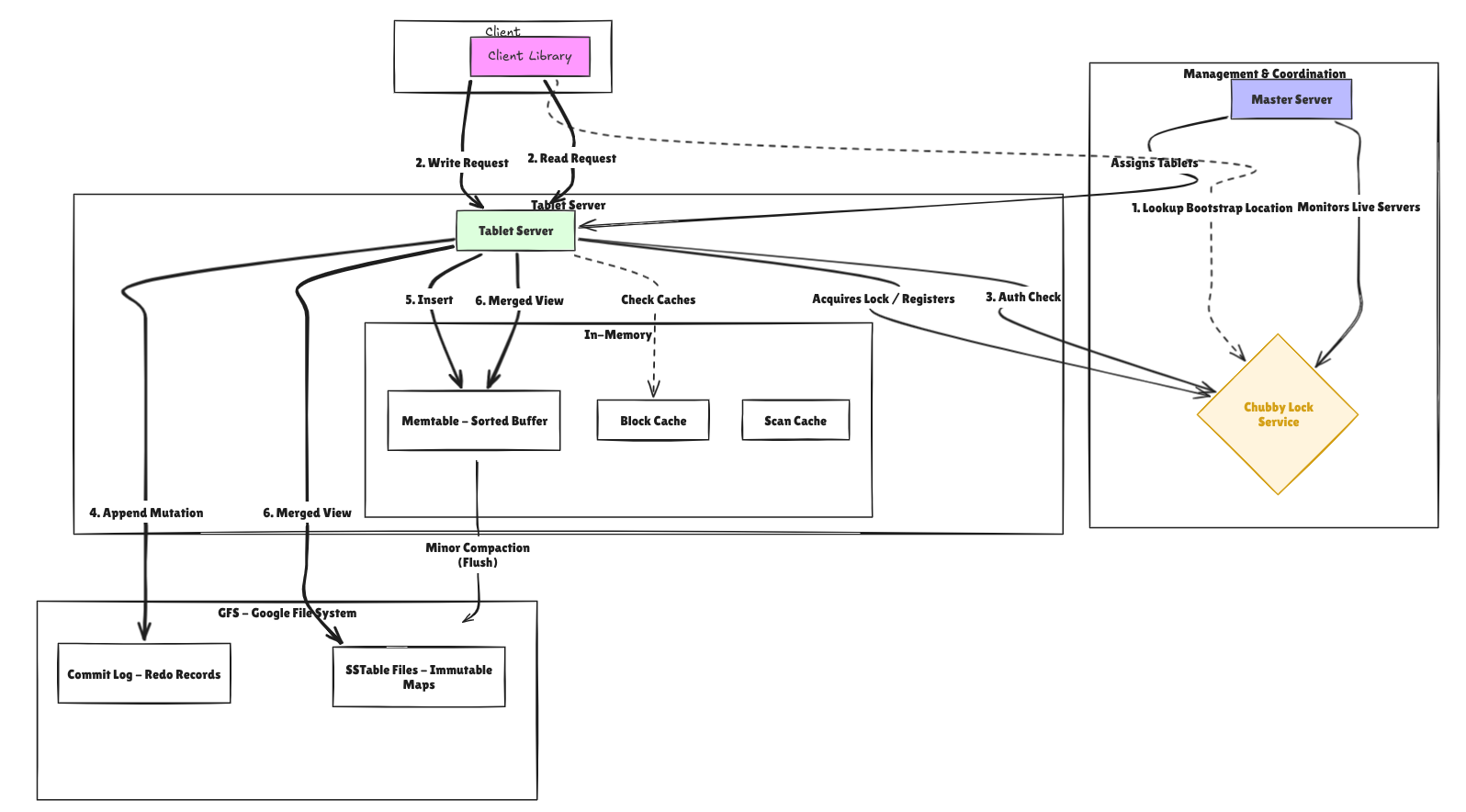

19. Data Flow Summary

Alright, let’s tie it all together. Here’s what actually happens under the hood when you do a single write, from your client call all the way to durable storage.

How the write operates

First, the client’s write request must reach the correct tablet server and be durably persisted:

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant Cache as TabletLocationCache

participant TS as TabletServer (ts-1)

participant Chubby

participant CommitLog

participant GFS

Note over Client,GFS: Phase 1: Write Request & Durability

Client->>TS: Put("webtable", "com.google", Column{"anchor","Google"}, "Google HQ")

TS->>Cache: findTabletServer()

Cache-->>TS: Cache hit → ("ts-1", "webtable[nil,nil)")

TS->>Chubby: Verify session (ACL check)

Chubby-->>TS: OK

TS->>CommitLog: Append(tabletID, cell)

CommitLog->>GFS: JSON encode LogRecord → /tmp/bigtable_gfs/logs/ts-1.log

GFS-->>CommitLog: seqNo = 42

CommitLog-->>TS: Ack (Write is durable)

sequenceDiagram

participant TS as TabletServer (ts-1)

participant Tablet

participant Memtable

participant Cache as ScanCache

Note over TS,Cache: Phase 2: Apply to Memtable

TS->>Tablet: Apply(cell)

Tablet->>Memtable: Insert(cell)

Memtable-->>Tablet: Binary search insert

Tablet-->>TS: Current size = 1.2MB

TS->>Cache: Invalidate("com.google:anchor:Google")

Cache-->>TS: Cache entry removed

Note over TS,Memtable: Memtable threshold: 4MB

Note over TS,Memtable: Current: 1.2MB (no flush needed)

When memtable exceeds 4MB, background goroutines handle persistence:

sequenceDiagram

participant TS as TabletServer

participant Tablet

participant Memtable

participant MinorBG as MinorCompaction Goroutine

participant MajorBG as MajorCompaction Goroutine

participant GFS

Note over TS,GFS: Phase 3: Compaction (Triggered when memtable ≥ 4MB)

alt Memtable size >= 4MB

TS->>MinorBG: Signal minorFlushCh

activate MinorBG

MinorBG->>Tablet: MinorCompaction()

MinorBG->>Memtable: Freeze current memtable

MinorBG->>Tablet: Create new memtable

MinorBG->>GFS: Write SSTable (Finish)

GFS-->>MinorBG: SSTable written

MinorBG->>Tablet: Register SSTableReader (newest first)

Tablet-->>MinorBG: Total SSTables = 6

alt len(sstables) >= 5

MinorBG->>MajorBG: Signal majorCompactCh

activate MajorBG

MajorBG->>Tablet: MajorCompaction()

Note over MajorBG,Tablet: Merge multiple SSTables

to reduce read amplification

deactivate MajorBG

end

deactivate MinorBG

end

And a read:

Every read starts with locating the tablet and checking the query result cache:

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant TS as TabletServer (ts-1)

participant Cache as TabletLocationCache

participant Tablet

participant ScanCache

Note over Client,ScanCache: Phase 1: Request Routing & L1 Cache

Client->>TS: Get("webtable", "com.google", Column{"anchor","Google"})

TS->>Cache: findTabletServer()

Cache-->>TS: Cache hit → "ts-1"

TS->>Tablet: Read(row="com.google", column="anchor:Google")

Tablet->>ScanCache: Lookup("com.google:anchor:Google")

ScanCache-->>Tablet: Cache Miss

Note over Tablet: ScanCache miss → Must read from storage layers

On cache miss, Bigtable reads from three storage layers in order of freshness:

sequenceDiagram

participant Tablet

participant Memtable

participant ImmMem as Immutable Memtables

participant SSTable

participant Bloom

participant Block

Note over Tablet,Block: Phase 2: Multi-Level Storage Read

Note over Tablet: Level 1: Active Memtable

Tablet->>Memtable: Get(key, maxVersions=1)

Memtable-->>Tablet: [Cell{value="Google HQ", ts=1234567}]

Note over Tablet: Level 2: Immutable Memtables (pending flush)

loop For each immutable memtable

Tablet->>ImmMem: Get(key)

ImmMem-->>Tablet: [] (empty)

end

Note over Tablet: Level 3: SSTables (newest → oldest)

loop For each SSTable

Tablet->>Bloom: MightContain("com.google\x00anchor\x00Google")

Bloom-->>Tablet: true (possible match)

Tablet->>SSTable: Binary search index

SSTable-->>Tablet: block 0 @ offset 0

Tablet->>Block: Decode block

Block-->>Tablet: [Cell{value="Google HQ", ts=999}]

end

Note over Tablet: Results collected:

Memtable: ts=1234567

SSTable: ts=999

Bigtable’s multi-versioning requires merging results from all layers:

sequenceDiagram

participant Tablet

participant Merger

participant ScanCache

participant TS as TabletServer

participant Client

Note over Tablet,Client: Phase 3: Version Reconciliation & Response

Note over Tablet: Collected results:

• Memtable: ts=1234567

• SSTable: ts=999

Tablet->>Merger: mergeCells(allResults, maxVersions=1)

Note over Merger: 1. Sort by timestamp desc

[1234567, 999]

2. Apply version limit

Keep only latest (1234567)

3. Apply tombstone rules

Merger-->>Tablet: [Cell{value="Google HQ", ts=1234567}]

Note over Tablet: Update cache for future reads

Tablet->>ScanCache: Store("com.google:anchor:Google", result)

ScanCache-->>Tablet: Cached

Tablet-->>TS: Cell{value="Google HQ", ts=1234567}

TS-->>Client: Cell{value="Google HQ", ts=1234567}

Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far, here’s a cheat sheet of everything we built and how it maps back to the paper. Turns out one Go file can do a lot.

| Paper Concept | Implementation |

|---|---|

| Sparse sorted map | CellKey ordering with CompareCellKeys |

| Column families | ColumnFamily, TableSchema |

| Multi-version storage | Timestamp in CellKey, mergeCells |

| GFS integration | Simulated GFS struct |

| Chubby integration | Full Chubby with sessions, locks, watches |

| Commit log (WAL) | CommitLog with sequence numbers and replay |

| Memtable | Sorted []MemtableEntry with freeze/swap |

| SSTable | Block format with index and bloom filter |

| Minor compaction | Memtable → SSTable flush |

| Major compaction | Multi-SSTable merge with tombstone elimination |

| Tablet split | Median-key split returning two new tablets |

| Tablet server | Background goroutines, merged read view, WAL |

| Master server | Election, assignment, failure detection, rebalancing |

| Three-level location hierarchy | Chubby → METADATA → user tablets |

| Client-side caching | TabletLocationCache with TTL |

| Per-row atomicity | Single-call batch mutations |

| Read-modify-write | Atomic increment and append |

The major simplifications versus a production system are: using encoding/json instead of a binary format, using a local filesystem instead of real GFS, using a sorted slice instead of a skip list for the memtable, and omitting network RPC (everything runs in-process). But the architecture, data flow, and algorithms are faithful to the original paper.

Similar blog posts:

In the next blog in this paper implementation series, I’ll implement the Google File System paper. Maybe even integrate to this implementation. Stay tuned! Subscribe to the newsletter if you haven’t yet.